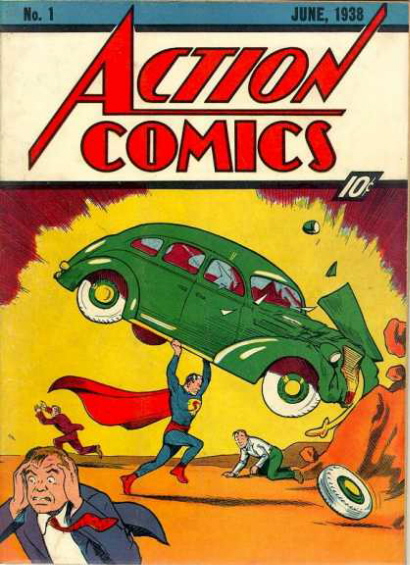

Coming from the generation that remembers the 5¢ candy bar, the nickel ice cream cone and the terrible shock when the price of a comic book, after several decades at a dime, increased to 12¢ in the early 1960s, it is hard for me to imagine shelling out $20 or more for a graphic novel. I sure wish my parents had used a Mercury dime and popped for an Action Comics #1 back in 1938 and put it in a safe deposit box for me. Then I wouldn’t worry about the price of a graphic novel. But, hey, I’ve been hanging out at Starbucks a lot lately, so that premium comic book doesn’t seem so bad next to a $4 frappucino. And I’ve bitten the bullet and given these luxury comics a try, some original stories, some adaptations of previous novels and some new looks at heroes from the past.

The biggest difference I’ve noticed between today’s graphic novels and the comics of my youth, next to the price, of course, is the dependence on pictures to tell the story with far fewer words. It is not uncommon to have full-page illustrations with just a word or two or even none. In addition, art tends to be more realistic and far less exaggerated than in the old Jack Kirby days. I really liked Jack Kirby, too, but these guys who are illustrating today’s graphic novels are scary good.

By the way I’m sure the folks who came up with the Comics Code back in 1954 are spinning in their graves over the words and pictures in today’s graphic novels. They would probably rise up in horror and curse the authors and illustrators, but rising from the dead; the word, horror; and cursing were forbidden in the Code.

So, with out further ado, here is the first installment of an old guy’s reactions to graphic novels.

The Crypt Keeper at EC would have been right at home telling you about Locke & Key: Welcome to Lovecraft (IDW, $24.95), written by Joe Hill with art by Gavriel Rodriquez. After the vicious murder of a high school counselor on the West Coast, his wife and three children move in with his brother in the old family mansion in Massachusetts.

The mother is doing her best to hold the family together, but she drinks too much; the older son is in a constant state of denial; the teenage daughter tries to be the stabilizing influence; and the younger son discovers a secret doorway, where he can temporarily die and turn into a ghost. He makes friends with a spirit who inhabits a well on the mansion’s grounds. Don’t expect a very nice spirit here. Meanwhile, one of the killers is on his way east.

Hill’s story is spare and as moody as one who has read Heart-Shaped Box and his short stories might expect, but there are unexpected touches of humor throughout, which relieve the tension just enough to let it build again.

Rodriguez’s art is terrific, making it hard to believe that the story and the illustrations didn’t come from one person. The book comprises the first five chapters of the story of the Lockes, with more to follow. I’m in for the long haul.

Adam Rapp’s Ball Peen Hammer, artwork by George O’Connor (First Second, $17.99), as the blurbs on the cover state, is “Not for gentle readers.” “The world is dying,” you see, in this dystopian future where a syndicate murders children and stores them in bags in a warehouse. And don’t expect things to get better from there. Even the Crypt Keeper would have been depressed by this one.

The book starts with nine pages in which the story is told almost entirely in pictures. The protagonist, a diseased young musician, says only one word, and not a pleasant word at that, as he struggles to start his day.

Eventually, he will meet up with an aspiring writer, an actress and one or two of those endangered children. The message that develops along with the tale is that there is definitely no future for artists, and. as the younger generation is wiped out, no future at all. There is nothing happy about Ball Peen Hammer, but, when it comes to building tension, establishing a mood and making readers think, this presentation succeeds on all fronts.

Part 2, about a pair of novel adaptations, follows soon.

Mark Graham reviewed books for the Rocky Mountain News from 1977 until the paper closed its doors in February 2009. His “Unreal Worlds” column on science fiction and fantasy appeared regularly for the paper since 1988. He has reviewed well over 1,000 genre books. If you see a Rocky Mountain News blurb on a book it is likely from a review or interview he wrote. Graham also created and taught Unreal Literature, a high school science fiction class, for nearly 30 years in the Jefferson County Colorado public schools.